Some title deeds relating to Tonbridge Town and Parish, 1476-1869

The conveyances concern property in the town and its rural neighbourhood, Hildenborough and Southborough, all within the ancient parish. Edited by C.W. Chalklin.

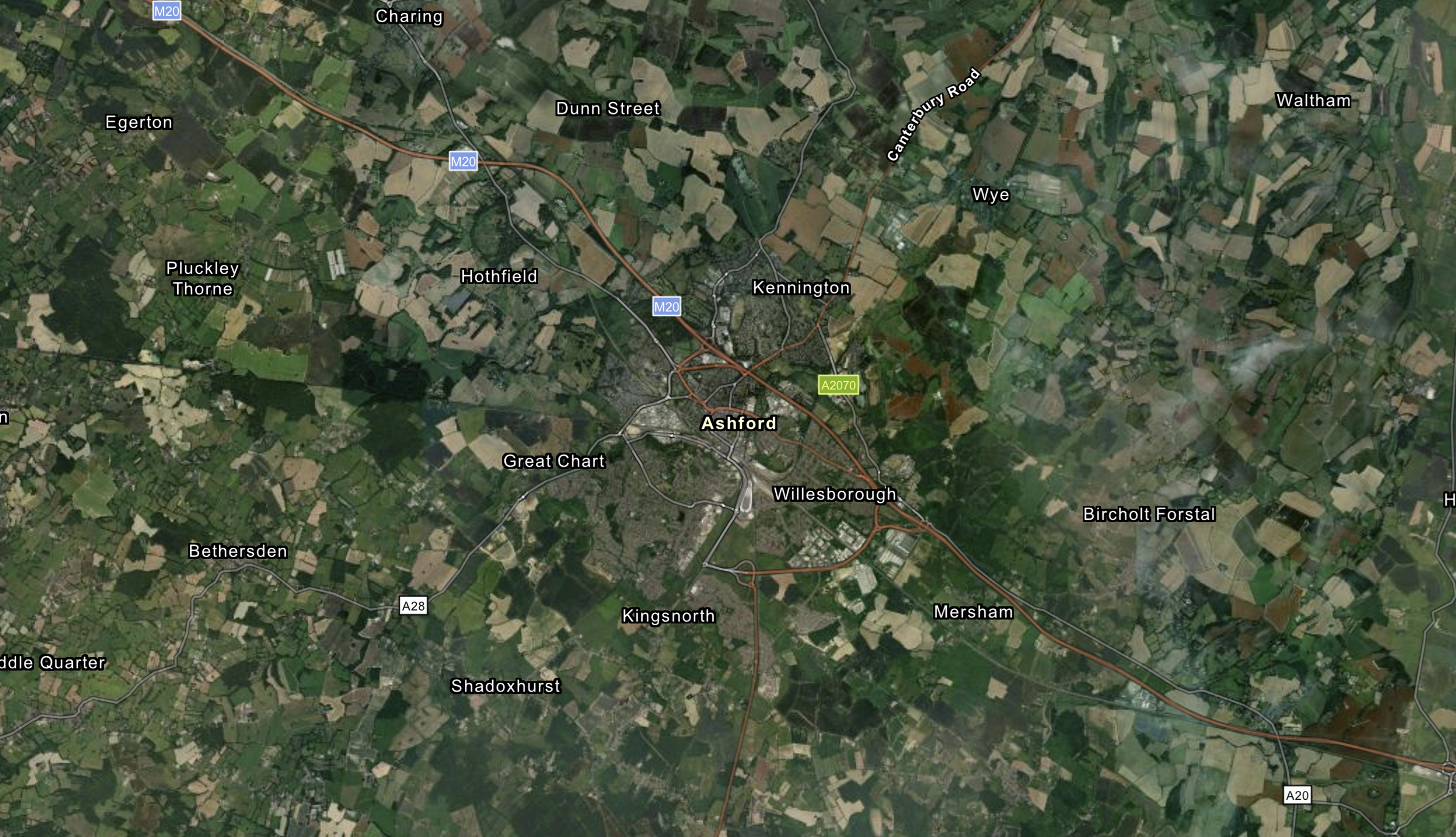

Ashford Quakers Registers - Births 1660 to 1732

Ashford Non-Conformists Church Minute Books/Registers - collected by the late Arthur Ruderman.

Catalogue of Harris Manuscripts relating mainly to Chelsfield 1503-1914

This extremely interesting collection of documents, ranging in date from 1503 to 1914, was accumulated over several centuries by the Styles, Burton, Aynscomb and Harris families.

Tags

- Accounts

- Adisham

- Alkham

- Ash-next-Ridley

- Ashford

- Aylesford

- Bekesbourne

- Betteshanger

- Biddenden

- Brenzett

- Bromhey

- Bromley

- Canterbury

- Capel

- Chalk

- Charing

- Charters

- Chatham

- Chelsfield

- Cliffe

- Cooling

- Cranbrook

- Custumale Roffense

- Cuxton

- Dartford

- Deal

- Dover

- Eastbridge

- Eastry

- Faversham

- Fawkham

- Feet of Fines

- Folkestone

- Food

- Frindsbury

- Gillingham

- Goudhurst

- Gravesend

- Haddenham

- Hadlow

- Harbledown

- Hawkhurst

- Hawkinge

- Higham

- Hoath

- Hoo

- Horton Kirby

- Hythe

- Ifield

- Inscriptions

- Ivychurch

- Lamberhurst

- Laws

- Lewisham

- Littlebourne

- Lydd

- Lyminge

- Maidstone

- Medicine

- Medieval

- Military History

- Modern

- Monasticism

- Monumental Inscriptions

- Newenden

- North West Kent Family History Society

- Northfleet

- Orlestone

- Preston near Wingham

- Rainham

- Ramsgate

- Records

- Ringwould

- Rochester

- Rochester Cathedral

- Saltwood

- Sandwich

- Shipbourne

- Shoreham

- Sittingbourne

- Snargate

- Snave

- Snodland

- Snodland Historical Society

- Stansted

- Stoke

- Stone in Oxney

- Stourmouth

- Stowting

- Strood

- Sturry

- Surveys

- Tenterden

- Textus Roffensis

- Tithe Commutation Surveys

- Tonbridge

- Westwell

- Wills

- Woolwich

- Wouldham