Front matter, Volume 142

2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

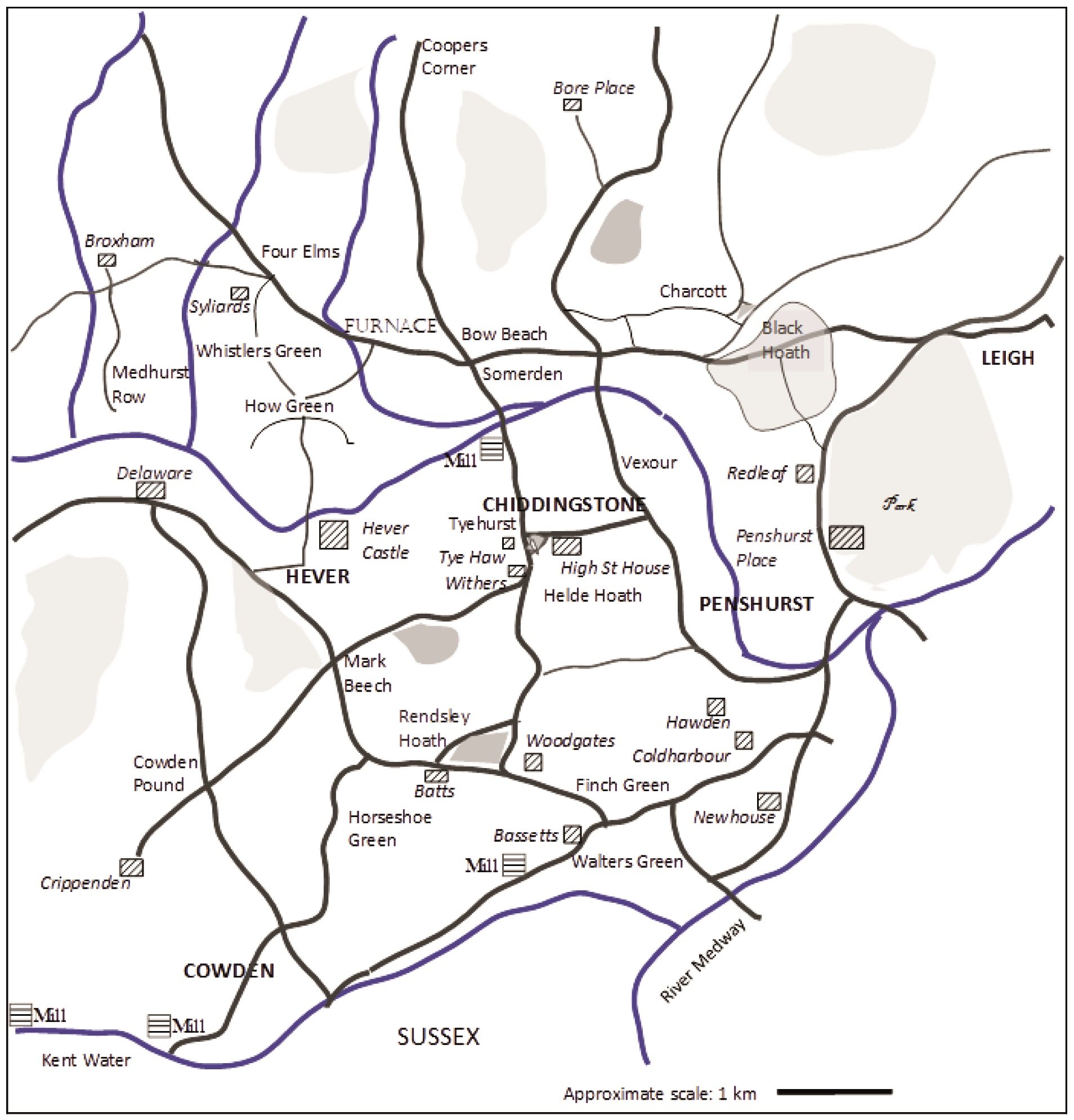

Gavelkind on the Ground, 1550-1700

Imogen Wedd, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Bigbury Camp and its associated earthworks: recent archaeological research

Christopher Sparey-Green, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

William Clinton, Earl of Huntingdon, and the county of Kent: a study of magnate service under Edward III

Matthew Raven, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

The middle/late Iron Age and Roman finds made by Antoinette Powell-Cotton

Vera and Trevor Gibbons, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

The Kentish associations of a great West Indian planter: Sir William Young (1725-1788)

P. J. Marshall, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Evidence of a late Iron Age/early Roman settlement and an early medieval strip field system at Shadoxhurst

Hayley Nicholls, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

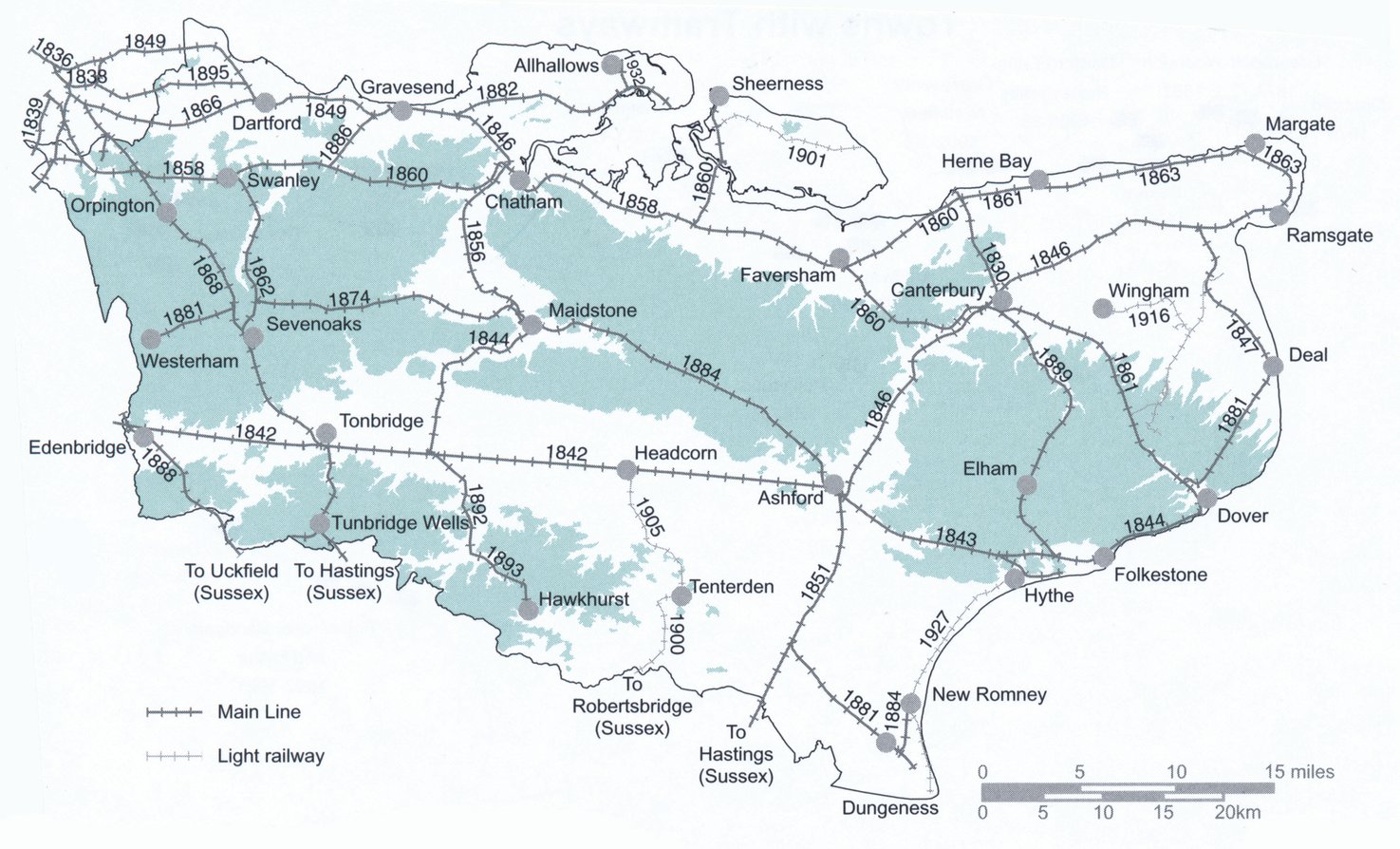

Rail, Risk and Repasts – The Dining Culture of the London, Chatham & Dover Railway, 1888-99

Iain Taylor, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

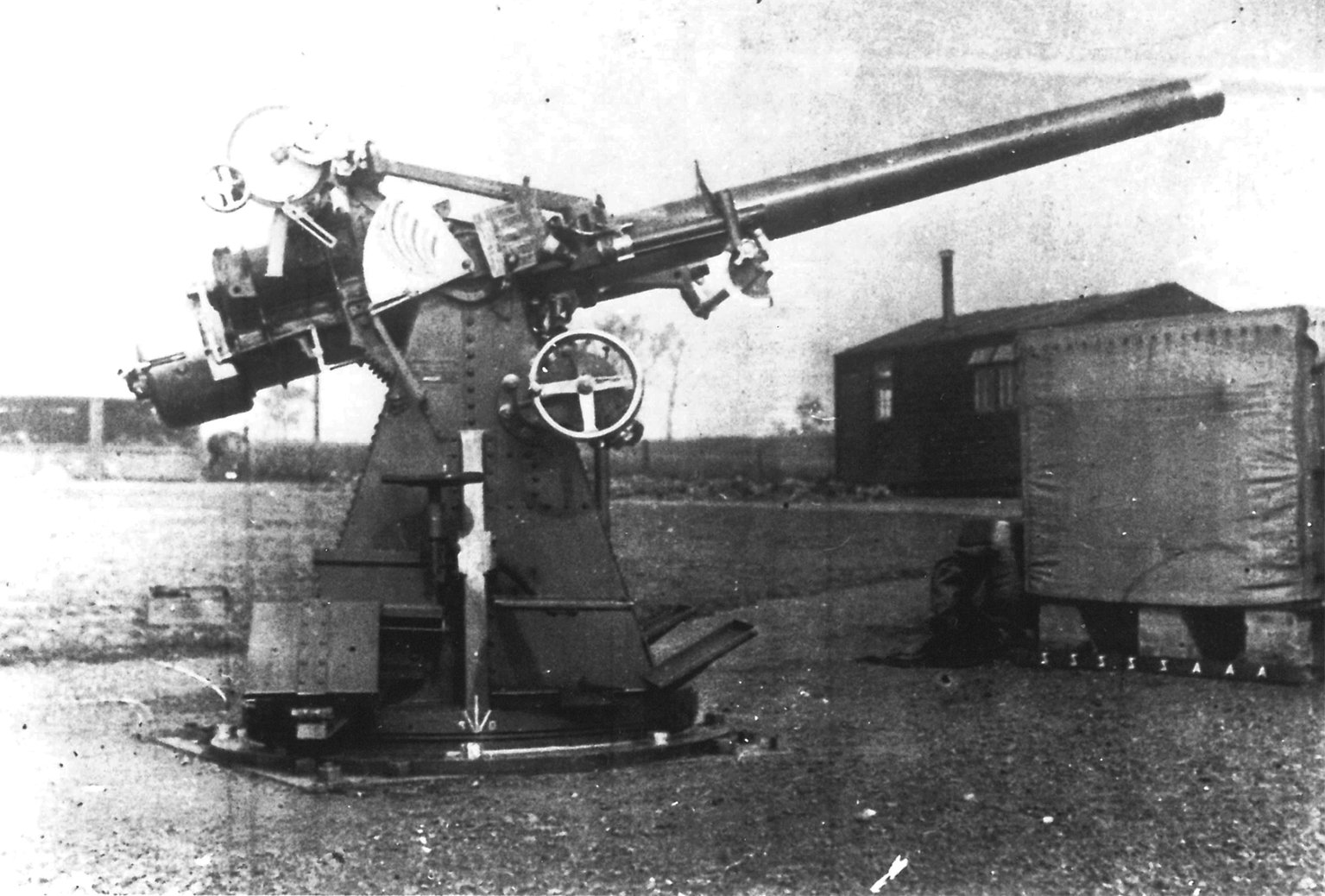

Kent’s twentieth-century Military and Civil defences. Part 5 – Swale

Victor T. C. Smith, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

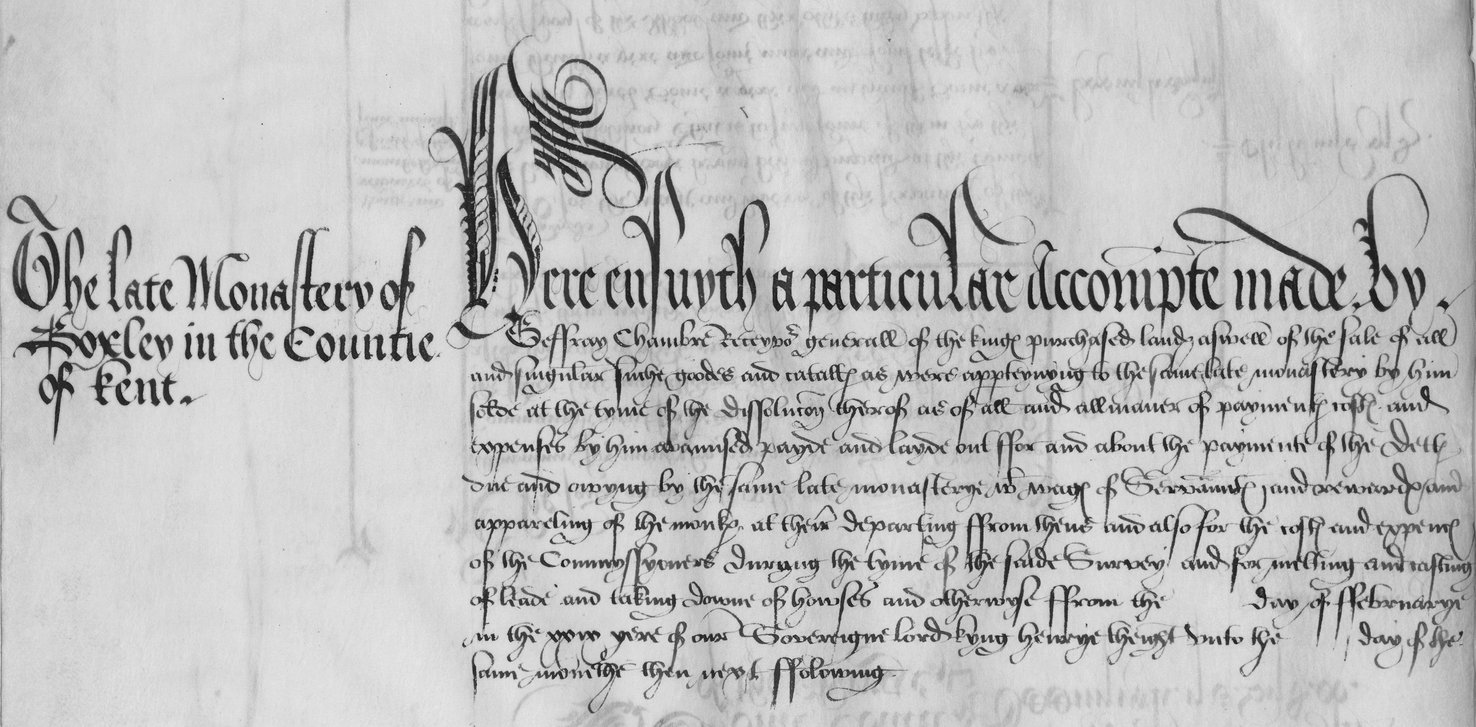

The Late Monastery of Boxley in the Countie of Kent

Michael Carter, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

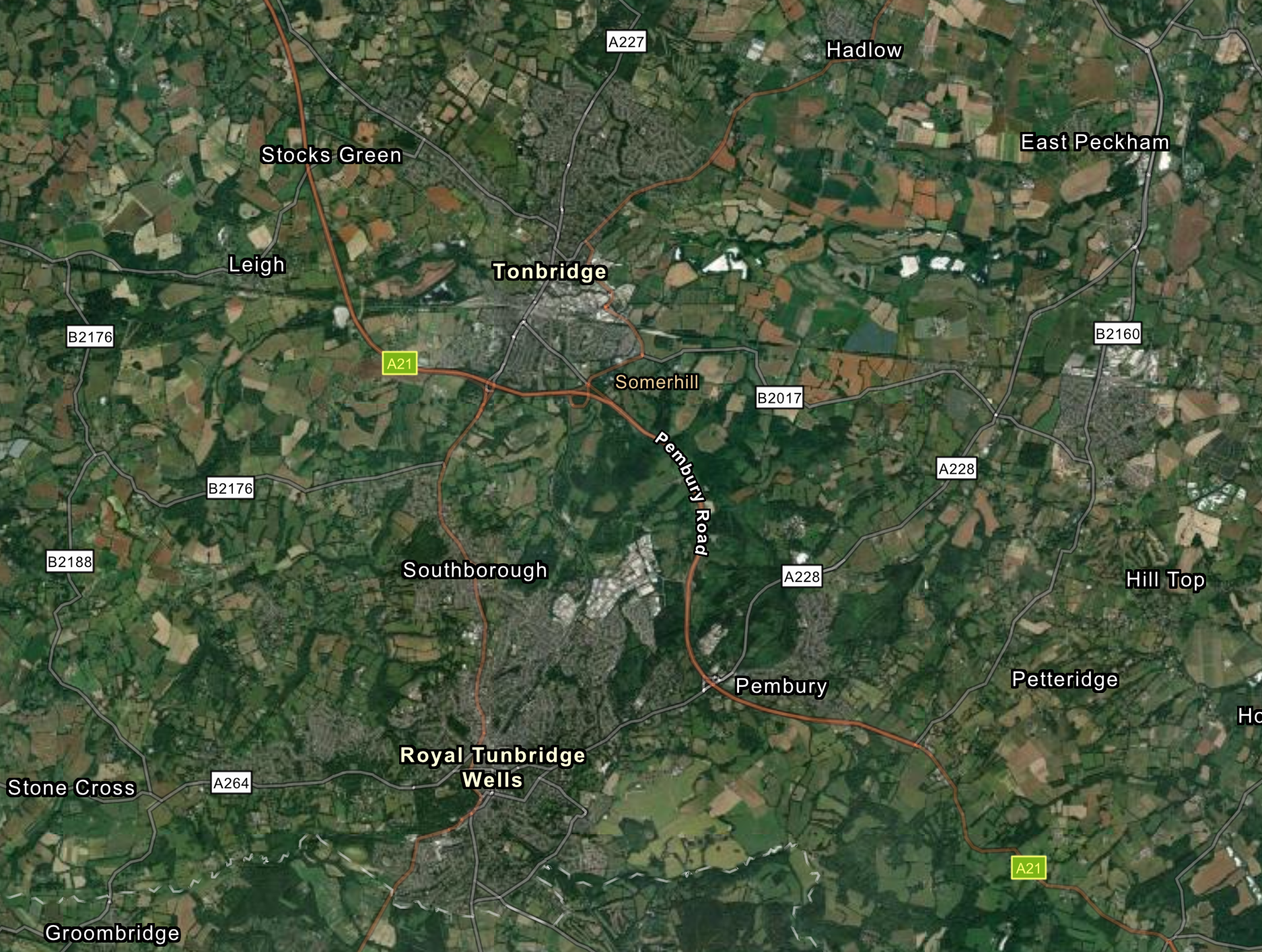

Prehistoric to Medieval Discoveries along the A21 Tonbridge-Pembury dualling scheme

Tim G. Allen, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

The Manor of Elverton in the parish of Stone next Faversham

Duncan Harrington, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

The Roman building at Chart Sutton revisited

Deborah Goacher, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

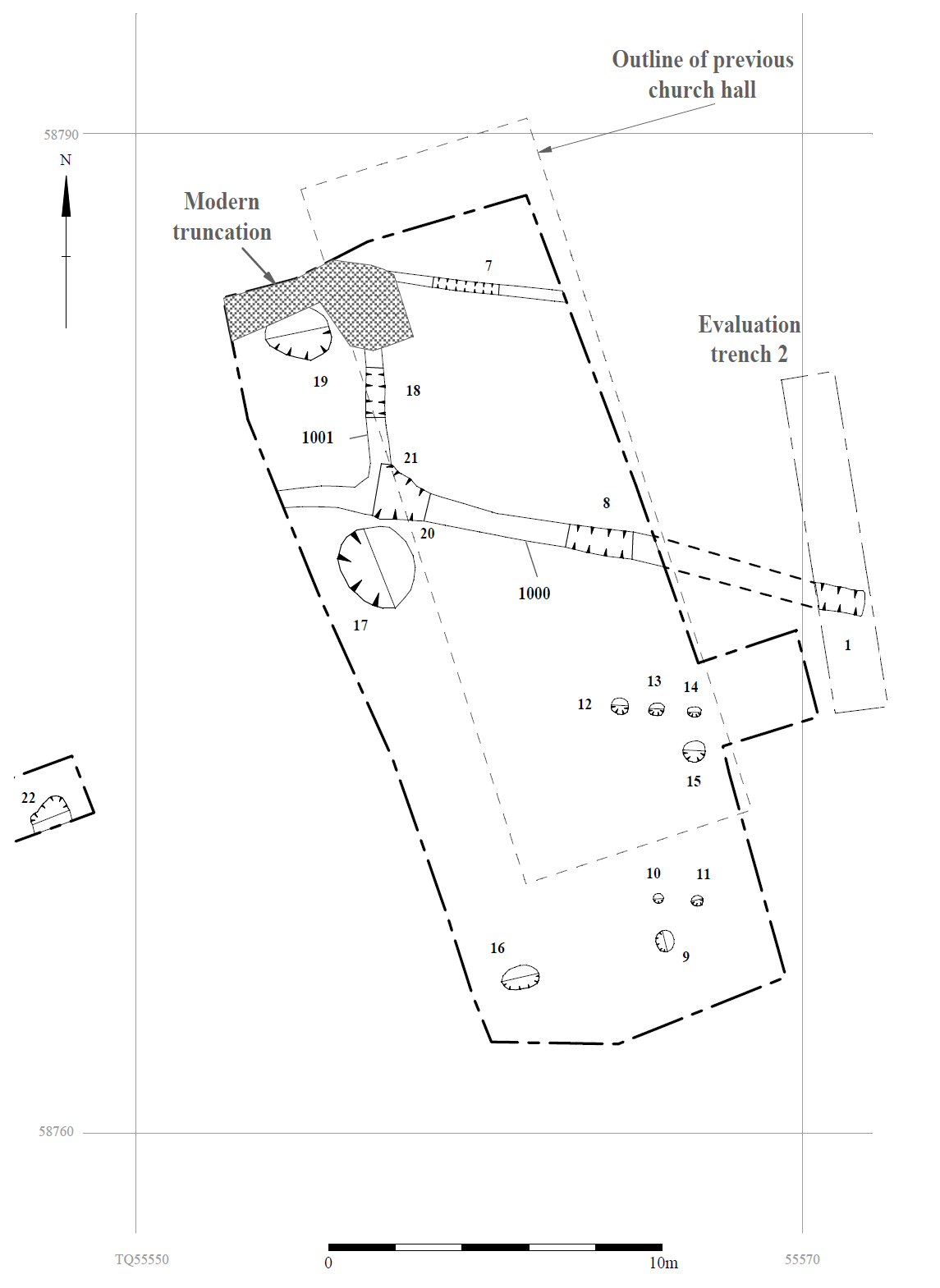

Evidence of Late Roman Settlement near the site of the Church Hall, Kemsing

Sean Wallis, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

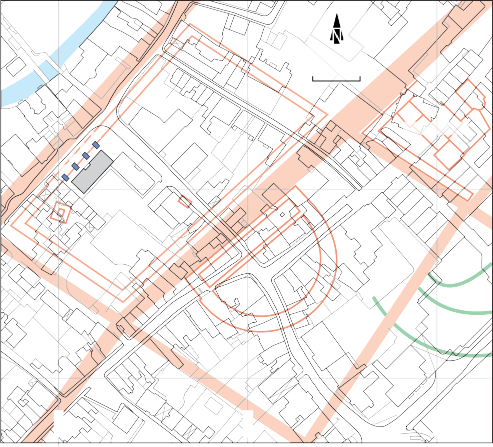

Near the heart of Romano-British Durovernum: Excavations at 70 Stour Street, Canterbury

Damien Boden and Jake Weekes, 2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Researches and Discoveries

2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Kentish Bibliography

2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Notes on Contributors

2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

General Index

2021, Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 142. Maidstone: Kent Archaeological Society.

Categories

- Articles

- General Indexes

- Lists of Contents

- Volume 10

- Volume 100

- Volume 101

- Volume 102

- Volume 103

- Volume 104

- Volume 107

- Volume 108

- Volume 109

- Volume 11

- Volume 110

- Volume 112

- Volume 114

- Volume 115

- Volume 116

- Volume 12

- Volume 120

- Volume 121

- Volume 122

- Volume 123

- Volume 124

- Volume 125

- Volume 126

- Volume 127

- Volume 128

- Volume 129

- Volume 13

- Volume 130

- Volume 131

- Volume 133

- Volume 135

- Volume 136

- Volume 138

- Volume 139

- Volume 14

- Volume 140

- Volume 143

- Volume 145

- Volume 146

- Volume 15

- Volume 16

- Volume 17

- Volume 18

- Volume 2

- Volume 20

- Volume 21

- Volume 22

- Volume 23

- Volume 24

- Volume 28

- Volume 31

- Volume 36

- Volume 37

- Volume 38

- Volume 39

- Volume 40

- Volume 41

- Volume 42

- Volume 43

- Volume 44

- Volume 45

- Volume 46

- Volume 47

- Volume 48

- Volume 61

- Volume 64

- Volume 65

- Volume 66

- Volume 68

- Volume 69

- Volume 70

- Volume 71

- Volume 72

- Volume 74

- Volume 77

- Volume 78

- Volume 79

- Volume 80

- Volume 81

- Volume 82

- Volume 83

- Volume 84

- Volume 85

- Volume 86

- Volume 87

- Volume 88

- Volume 89

- Volume 9

- Volume 91

- Volume 92

- Volume 93

- Volume 94

- Volume 95

- Volume 96

- Volume 97

- Volume 98

- Volume 99

Tags

- Agriculture

- Appledore

- Ashford

- Ashford Archaeological Society

- Bexley

- Bromley

- Canterbury

- Chatham

- Church History

- Churches

- Cliffe (Hoo)

- Cobham

- Cooling

- Cranbrook

- Darent

- Darenth

- Dartford

- Dartford & District Archaeological Group (DDAG)

- Dartford Historical and Antiquarian Society

- Deal

- Defences

- Dover

- Earthworks

- Eastry

- Eccles

- Edenbridge

- Faversham

- Fieldwork and Research Grants

- Folkestone

- Frindsbury

- Genealogy

- Gravesend

- Gravesend Historical Society

- Hasted Prize

- Heraldry

- Herne Bay Historical Records Society

- Hoo

- Hythe

- Ightham

- Industrial

- Inventories

- Iron Age

- Isle of Sheppey

- Isle of Thanet

- Isle of Thanet Archaeological Society

- KAS Collections

- KAS Library

- Kent Archives Kent History and Library Centre

- Kent Family History Society

- Knole

- Little Chart

- London

- Lullingstone

- Lyminge

- Maidstone

- Maidstone Area Archaeological Group (MAAG)

- Maidstone Museum

- Maps

- Margate

- Maritime

- Medieval

- Megaliths

- Memorials

- Military History

- Milton

- Minster-in-Thanet

- Modern

- Monasticism

- New Romney

- Nonington

- Orpington and District Archaeological Society (ODAS)

- Ospringe

- Otford

- Plaxtol Local History Group

- Prehistoric

- Ramsgate

- Reculver

- Richborough

- River Medway

- Roads

- Rochester

- Romney Marsh

- Sandwich

- Sarre

- Sevenoaks

- Shoreham

- Shorne

- Sittingbourne

- Springhead

- The Faversham Society

- The Woolhope Club

- Tonbridge

- Tonbridge Historical Society

- Trust for Thanet Archaeology

- Upchurch

- Weald

- Westerham

- Wills

- Wingham

- Wye Historical Society